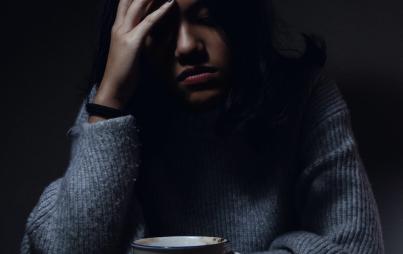

This is what PMDD looks like. It's also what depression looks like.

I could go a week, maybe two, feeling well, and then something would happen. I saw the cycle the psychiatrist was pointing out to me. I didn’t want to see it, but there it was.

I’ve spent years interpreting the nature of my depression. As a teenager, I was moody and artistic, but finding myself. In my early 20s I oscillated between reckless and reclusive. I took my first SSRI at 25, with a shaking hand across the table from my boyfriend at a vegetarian restaurant in Berkeley. I lifted a cold glass of water and ingested what felt like relief. He looked at me and said with empathetic and expectant blue eyes, “I hope this works.” It did work. Kind of. For a while.

Prozac was my companion for three years, when the gray haziness of my mental state intensified again and I went to a psychiatrist, desperate for something else to turn the pain down. She told me the escalation of my depression was either 'Prozac poop-out' (an actual term used among mental health professionals which means a point at which SSRIs just stop working), or that my depression was actually Bipolar II, the sibling of Bipolar I, in which sufferers experience the deep lows of the condition but only half-highs called hypomania.

I thought about my life since my depression resurfaced in full force. I could go a week, maybe two, feeling well, and then something would happen. I saw the cycle the psychiatrist was pointing out to me. I didn’t want to see it, but there it was. She prescribed me a mood stabilizer, but while standing in line at the pharmacy I didn’t feel hopeful that I might get some relief. I felt sicker than ever.

The medication didn’t do much. I still went through the same cycles of deep depression and relative wellness (punctuated with occasional bursts of creative energy I was understanding as hypomania and evidence of my illness). I knocked on the door of another psychiatrist, desperate once more for answers. This doctor shrugged at the Bipolar II diagnosis and put me on another antidepressant.

That was nearly five years ago, and since then I’ve been faithfully filling my prescription every month despite still being flung through the ups and downs of a mental illness I was increasingly despondent over. No medication seemed to really work, so I started to believe I was responsible for my own sickness. While I professed the notion in public that mental illness is akin to physical illness, and therefore no one is at fault for having to cope with it, in private I hurled all the blame in my own direction.

Now weighted with the extra burden of feeling as though I had done something to cause my stubborn depression, I sought redemption more fervently. I tried talk therapy, Chinese medicine, and strange diets I gleaned from 4 a.m. Internet searches. I studied the Enneagram and read Viktor Frankl. I kept a dream journal. I collaged, I wrote, I listened to podcasts on Buddhism, and I tried forcing myself to be more social. Every solution felt possible for a day or two, maybe a week. For some period of time I felt the shadow of strength return. But quickly I would crash and the dreaded morning would arrive when this solution, or that one, would seem foolish, and I all the more foolish for believing in it.

I was incredulous when a psychiatrist recently took my history and prescribed me a birth control pill, Yaz. He told me my depression was consistent with Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD), which can cause large mood fluctuations during ovulation and for 1–2 weeks before menstruation. He told me that all the solutions I tried were predestined for sabotage by my hormonal system. The problem was never me — it was my hormones. I sat flabbergasted, at once relieved that there might be a real solution, and also skeptical that I wasn’t somehow to blame. I took the birth control pill he prescribed (FDA approved to treat PMDD), and in one week in I felt an emotional foundation return to me that I can’t remember having since I was a child. I guess this is what healthy people feel like.

PMDD diagnosis and treatment have changed my life. I’ve been more productive since being on the right medication, and have the emotional well-being to tackle problems I’ve been trying to solve for years. What’s most important, though, is that I’ve slowly relieved myself of the burden of feeling like I caused my own depression. It was a happy accident that I found the right doctor, diagnosis, and treatment. I’m grateful for it, but also aware that I suffered too long with a treatable condition.